BY ALEJANDRA BORBOLLA

Buñuelos

December in Mexico is about eating, sharing and caring. One of the most important things about Mexican food is dessert, and even though I don’t write much about it, I think it’s a good opportunity now, calorie counting being tossed to the winds and all.

Buñuelos is a recipe as old as colonized Mexico. One of the oldest known recipe books belongs to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a poet, dramatist, scholar and nun who was born around 1651. Her mother was a creole, and her father Spanish, but they did not have a large income. From when she was a little girl, she was hungry for knowledge, mostly self-taught from burying her nose in whatever book she could find. She also taught herself to read when she was three years old, or so the story goes. This was a time when girls were not allowed to go to school. Her mother knew she was bright, so she sent Inés to Mexico City to live with relatives. She was called to be a lady-in-waiting in the court of the viceroy’s wife.

A few years later, she was at the point where she either married or became a nun. So, she became the latter. We don’t know what was going on on the boyfriend front, but apparently not much. She joined the barefoot carmelitas but only stayed there four months, because she became sick. After recovering, her stark room at her new convent became the meeting point for intellectuals and poets, and Luisa Manrique, another viceroy’s wife (who, rumor has it, had a huge girl crush on María Inés). In her room, she also performed scientific experiments and had an amazing collection of books.

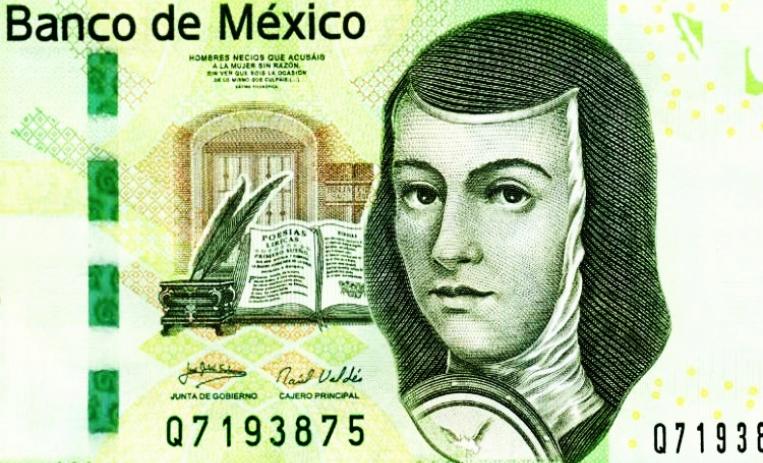

Sor Juana was well known for many things, most of those controversial. Most men who were in the same niche as her would publish “pseudonymous” letters trying to convince her to stick to her religious duty rather than using her brain. She wrote mostly poetry, about love, erotism, (She’s a nun, what does she know? Possibly her reason for going into the convent should be looked into.) She also wrote about morals and psychology. (One of her most important poems is written in tiny mice type on the 200 peso note, along with her portrait, which we’re hoping was taken on an unusually bad day).

But today we’re talking about this iconic woman because along with her other talents, she was a great cook. Her recipes were perfectly aligned with poetry, and delicious. Her culinary expertise, however, started at her family’s home back when she was a little girl, before all the nunsense. (haha, see what I did here? Nun-nonsense? I’m hilarious!)

The cooks at the hacienda kitchen were indigenous women from Oaxaca, so she grew up with both Spanish and indigenous cuisine.

Buñuelos de rodilla are a special buñuelo, which grandmothers used to shape with their bare knees, literally. In the olden days, buñuelos were actually called “puñuelos” because they were kneaded with the fists, called puños. The heritage form this dish comes from Iberian Christians, aka Spaniards, who had several recipes, including cheese, rice, pulque and milk.

Buñuelos were invented by the working class of the southern Spanish peninsula looking for a cheap, sweet, warm treat they could have in the winter when the economy wasn’t exactly thriving.

Every state has its own buñuelo recipe, ranging from bright orange colors, sugar coated or syrup, fried in lard or oil, served in corn husks or in paper. (Remember what I keep telling you: Mexican cooking is very regional.) Buñuelos are a sweet treat that is usually found around the church square of cities and towns, sold by street vendors at special times like Christmas, revolution day, independence day, day of the dead, etc.

In Oaxaca, buñuelos are eaten on a plate that will be thrown and shattered on the floor later, once it breaks in a million pieces, a wish will be granted for the next year. It’s not every state that observes that tradition.

Big batches are the usual when making buñuelos, because even though they are very cheap, it is very much worthier to make a lot of them at one time, because it’s not like people are going to eat just one, trust me.

To compliment this recipe, I’ll give you a short, sweet drink too, which is atole de masa, a thick hot drink that is not too sweet to balance out the flavors. Atole and buñuelos go together like mash and gravy. This is a completely Mexican drink, which was made ceremoniously by the Aztecs, and some rural communities still drink it in their every day lives. Sometimes, a cup of atole is all they have throughout the day, until they come home to have a hearty meal. The main ingredient is masa, the dough that is the base for tortillas.

For the Buñuelos:

2 cups of all-purpose flour

2 cups of sunflower oil

4 oz of water

½ stick of butter

½ teaspoon of star anise

3 tablespoons of sugar

1 pinch of salt

1 pinch of cinnamon

How to:

Shift flour and sugar together, along with the salt and cinnamon.

Heat up some water in a pot, and add the star asnise. This liquid will be what gives buñuelos their signature taste and fragrance.

Add the butter to the dry ingredients, preferably at room temperature and start mixing. Using your hands will be faster and easier. Wash them first.

Once the butter and flour are mixed together, start adding tablespoons of the anise water, slowly, until a firm and homogeneous dough is achieved. The perfect consistency is when the dough is not sticky anymore, and is stretchy.

Leave the dough to rest for ten minutes, sprinkle with a lot of flour to prevent a crust from forming.

Once the ten minutes have passed, form little balls about the size of a lime, to make the buñuelos. (I’d recommend to slather some oil on your hands)

With the help of a rolling pin, form the buñuelos (You can try and shape them with your knees, but I don’t think you’ll make it.

Once you have formed the buñuelos, and are about as thin as a folded paper, you can start frying them.

Sprinkle with sugar and cinnamon.

Atole de masa

Ingredients:

½ cup of masa, can be store bought or made from maseca.

4 ½ of warm water or milk

1 stick of cinnamon

1 teaspoon of vanilla extract.

2 small cones of piloncillo or 1 cup of sugar (it’s not meant to be sweet, but you can add more to your taste)

How to:

Dissolve the masa in a cup of milk or water, depends on what you’re using.

Simmer the rest of the water or milk in a deep pot, and slowly add the dissolved masa.

Add the cinnamon, vanilla, sugar or piloncillo and bring to a gentle boil.

I am saving this Buñuelo recipe and the Atole for Christmas 2020. Thank you. I too have been eating Buñuelos topped with Cinnamon Sugar ever since I was a little girl, but mom would also make Anise Tea and the Atole de Masa. Thanks for sharing this beautiful story of Sor Juana.